If you work in the Earth sciences, as many of our users do, then you probably don’t come across the term “Dual Use” very often, if at all. Yet for the vendors that supply this community, it is a very significant term and has a large effect on where we supply our instruments to. I thought it would be worthwhile explaining a little about what this term means, and how it affects Isotopx and our contemporaries.

Firstly, what does it mean? According to the European Union, the definition is:

“Dual-use items are goods, software and technology that can be used for both civilian and military applications.”

You can read more on the EU website here.

The definition exists so that governments can control when and where items that fit into this category are exported. For example, if there is a conflict between nations then some governments may want to restrict the export of dual use items to one or more of those countries, even if the intended use may not be related to the conflict.

If your company makes handguns, for example, then you would expect your government to want to have a say in where they get shipped to and who will use them. But in many cases, it’s much more complicated than that. What about a computer chip that could be used to make video games run really fast, but could equally be used to guide a missile? And what about software that could be used to guide that missile? Yes, these are export controlled items as well, and may be classed as dual use.

Taking this one step further, what about the knowledge of how to use the computer chip and software to guide the missile? Actually, that knowledge, for example in the form of technical manuals and guides, may be export controlled too.

You’ve probably guessed how all this pertains to isotope ratio mass spectrometers. Whilst they are commonly used to measure neodymium or argon isotope ratios for geochronology and other Earth science applications, they can also be used to measure the isotope ratios in actinides. The lazy example here is that uranium for a nuclear reactor needs to be enriched in the 235U isotope, as naturally occurring uranium just won’t cut it; as we all know it has less than 1% 235U.

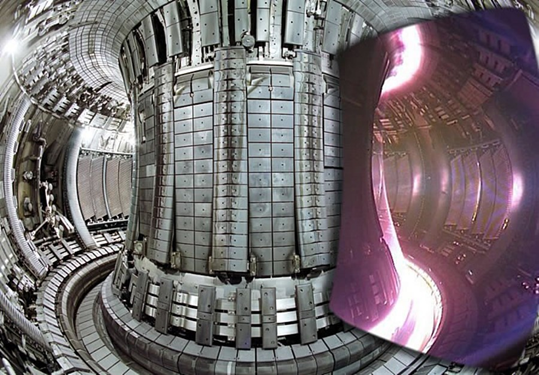

At some stage, the reactor fuel must be analysed to ensure that the ratio of isotopes in the uranium fuel pellets is correct. Obviously, I’ve hugely simplified the process. There are literally dozens of other isotope ratio measurements commonly made in the nuclear sciences; for example some of the materials used in shielding or containment can become enriched in unwanted isotopes through processes such as neutron bombardment. And it’s up to the reactor operators to characterize these materials. Things will get a lot tougher when fusion reactors come online and there will be a requirement to measure the hydrogen isotope ratios (H/D/T) in extremely challenging environments.

Gratuitous image of the ITER fusion reactor in France, image owned by ITER

That covers the “civilian” use of isotope ratio measurement techniques in the nuclear sciences, but of course they also have an equivalent role in non-civilian applications. Again, the nuclear material needs to be enriched in certain isotopes, and needs to be characterized isotopically, requiring isotope ratio MS. And any site producing those enriched isotopes needs to be constantly monitoring for environmental contamination, again requiring isotope ratio techniques.

What governments want to know is: if this isotope ratio mass spectrometer is shipped to a supposedly civilian nuclear power site, is there a possibility it will be diverted to a non-civilian site? How can they be sure of the destination? Governments primarily rely on intelligence. A governmental department needs to make an informed decision about what the risks are, based on a huge number of factors such as prior experiences, transparency of the end user country/lab, current geopolitical events and so on. Governments really do have a “black list” of labs that they are concerned about and won’t export to.

What about from the Isotopx point of view, how do the vendors handle the “dual use” complication? Firstly, we have our own screening processes based on prior experiences and our own ethical leanings. For example, if we have even the slightest concern that a mass spectrometer may be used for an application that the end user isn’t disclosing, then we’ll decline to trade. I am sure our competitors feel the same way. We’ve also declined to trade when we have felt that the end user lab or country would not be a totally safe environment for our engineers.

Once we’re happy with the proposed end user and application, the next step is that we contact the UK Government and request an “export license”. This is a document that allows freedom of passage for the instrument to the stated end user. This process can’t be started until we receive the purchase order from the customer, so naturally it can affect the timing of delivery for the customer. Receiving the license can either be really straightforward (if the lab is well known to the UK government and considered low risk) or can take many months if research is needed. So, in some cases it can be a waiting game, and we can’t move forward with the order until the export license is received.

Are there any short cuts? Normally, no. But if a laboratory is under the control of the IAEA (website link here) then governments do tend to look favourably at export controls. We’re in agreement with this policy – if we have doubts about the authenticity of a lab then the involvement of the IAEA does give us confidence.

Fortunately, the whole process does seem to work well, and in the most part we receive the green light from the UK government quite quickly. We interact with the relevant departments in the UK quite often, and they have been extremely helpful and encouraging.

Just keep in mind that even if your lab is a high-profile Earth science lab with absolutely no connection to nuclear science applications, we still need to go through the same process. So if you hear from us or indeed another mass spectrometer manufacturer that a delay is due to “export control”, then now you know why!

As always, please send me your thoughts and comments (Stephen.guilfoyle@isotopx.com).